Last summer, during our very first art fair (when Fading Nostalgia was but a mere twinkle in our eye), we realized while showing Chris’s night photography, we were going to have to explain how exactly the colored lights glow inside these abandoned houses, structures and cars. Obvious, but Chris has been doing this for so long, perhaps he took his knowledge of the seemingly magical secret for granted. As patrons glanced over Chris’s work, one of us would interject: “So what you see here isn’t Photoshop….we actually go inside with colored flashlights….” We continued on to describe the equipment, mention the full moon, discuss the long exposure and point out the star trails. We watched intently as the wheels turned inside their minds. Witnessing the moment each person arrived at his or her own “ah ha! moment” never got old. I don’t have children, but I can only assume it is similar to when parents explain some simple scientific happening to their kid and see his or her face light up with understanding. Interestingly enough, I’d say about 85% of these passers-by assumed it was indeed Photoshop or some kind of computer manipulation. And a lot of them would admit they were glad we informed them it wasn’t. So when this summer’s first art fair rolled around (Madison’s Art Fair on the Square), Chris and I printed out and posted a little sign with a short explanation:

No Photoshop! [What is Light-Painting?]

“Every color you see is created onsite by our own hands using flashlights, strobe lights, and colored theater gels. The camera shutter remains open 2-9 minutes, while the full moon or our own hand-held lights expose and light up each building, wall, window, or structure. Every composition requires tons of repeated experiments, patience, and venturing into rickety buildings and vehicles before we get the final shot. Long drives, late nights, bugs, animals, frozen toes, and an unexpected roll-in of thick cloud-cover make each and every single adventure a tale to tell.”

Of course, not everyone wants to read a lengthy explanation, so as patrons perused, we continued to interject: “So what you see here isn’t Photoshop….we actually go inside with colored flashlights….”

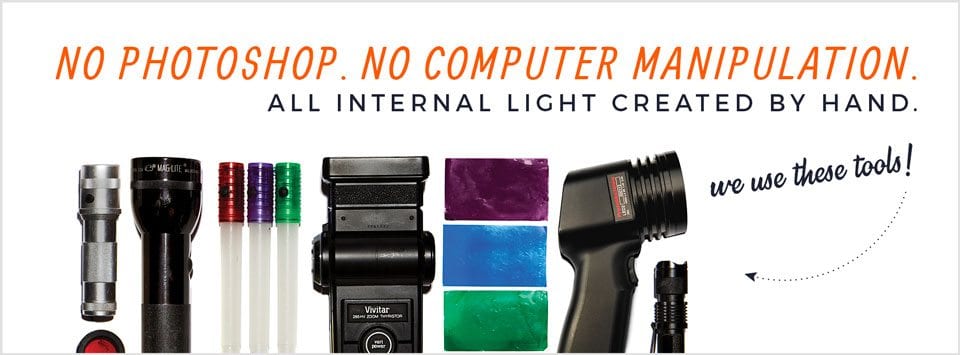

So at the Midsummer Festival of the Arts in Sheboygan the following weekend, we decided to make smaller, more simplistic signs to post strategically throughout the booth:

More people caught these signs. We would watch carefully as they pointed to the words and audibly question, “Wait no Photoshop??” then proceed to glance around to find one of us to ask how we do it.

Meanwhile, it dawned on me that the entire near-year FadingNostalgia.com has existed, we never truly explain the process to those who stumble upon this website! So 85% of our visitors could think it’s all computer trickery! That is just no good. So with that said, welcome to the first in a three-part series that will speak to the history of night photography, the light-painting process and equipment photographers use, as well as an in-depth look at one of our most memorable light-painting experiences.

So, now that you’ve read the little synopsis we’ve provided to our art fair patrons, you know the basics: Full moon, colored flashlights, long exposure. Here are a handful of fun facts about the history of night photography and light-painting:

The history of night photography goes back nearly to the advent of photography itself! But it wasn’t until the 1880s, with the invention of the gelatin dry plate negative (formerly a wet process, limiting exposure time), that photographers were able to develop longer exposures. In the 1890s–well over a century ago—Alfred Stieglitz began to capture and develop New York City night-scapes through long exposures.

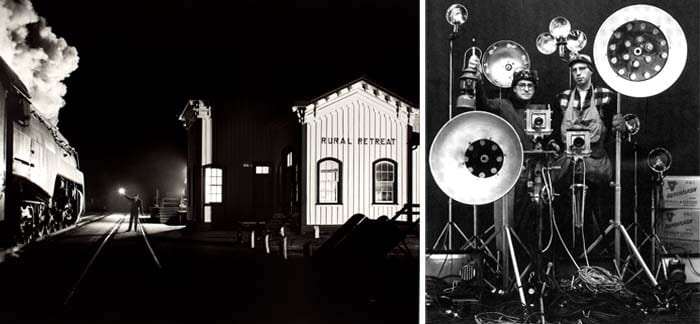

The availability of electricity gave way to the invention of larger lighting contraptions. Many years after flood-lighting became standard in the movie industry, O. Winston Link ran with this idea in the 1950s in order to create his own unique photographs. Link would set up several of these flood-lights to flash at steam engines passing through various landscapes under the heavy cloak of night. Complex productions to say the least, Link popularized this type of night photography and light-painting using simple and even cozy settings and imagery.

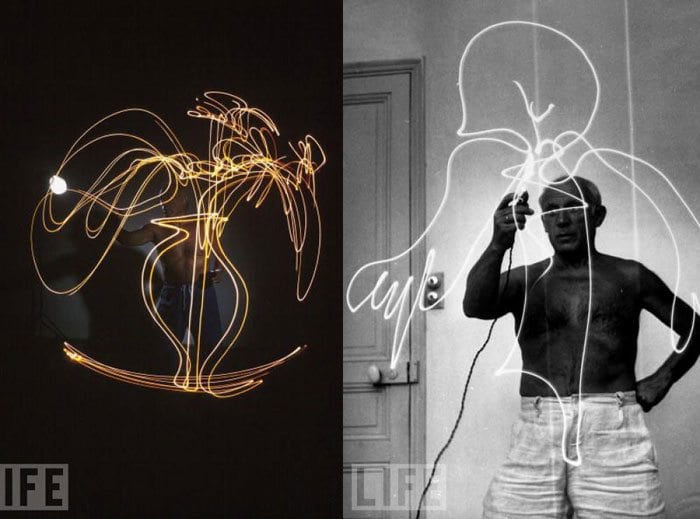

In 1949, Life Magazine photographer Gjon Mili captured a series of graffiti-style light-painting photographs of Pablo Picasso, all inspired by images Mili showed Picasso of ice figure skaters twirling and leaping in the dark with small lights on their skates. Over the past half century artist/photographers like Eric Staller, Michael Bosanko and Evan Sharboneau aka Photo Extremist take this type of light-painting to a whole new level.

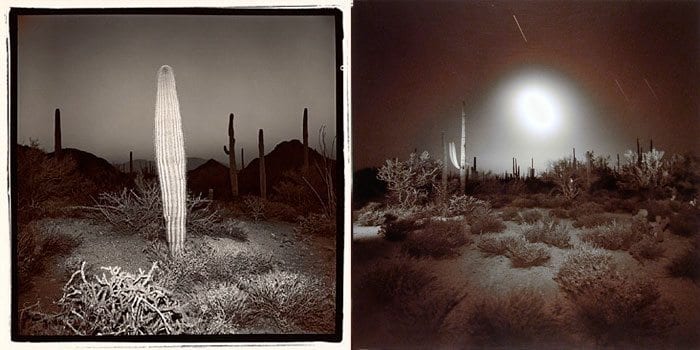

Throughout the mid-to-late century, photographers everywhere began to capture landscapes at night: the glow of city life, the long paths of car head- and tail-lights along the highway, the arched trails of stars as the earth moved along its axis. In the ’70s, Richard Misrach captured the haunting and barren landscapes of the desert night, complete with star trails. Interestingly enough, one of his more recent night photos is currently one of the world’s most viewed photos.

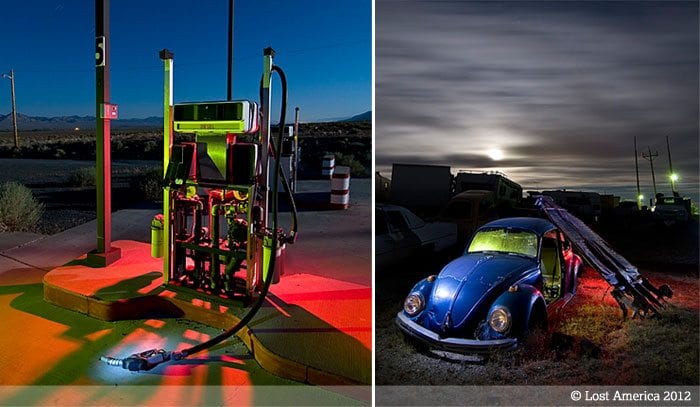

In the late ’80s, Troy Paiva–aka Lost America–combined his passion for night photography and exploration of the deserted American southwest to pioneer the light-painting technique Chris uses today. With a simple colored flashlight and a long exposure, Troy not only put a new surrealistic spin on a classic photographic genre, but spearheaded a new movement that made professionals and amateurs alike look at abandonment in a way that is both unique and even emotionally engaging. Believe it or not, Troy started light-painting with a film camera. In other words, no checking of any LED display to make sure you got the right shot. It’s do-or-die and you might just come home with a bunch of black photos if you don’t fully grasp the importance of film reciprocity, timing, light intensity and light physics! It’s hard to fathom, but if there’s one way to learn how to light-paint, analog seems pretty tops.

Diesel Number 5 – Schurz, Nevada & Far From Wolfsburg – Searchlight, Nevada | Lost America (Troy Paiva), 2010

Around 2005, Chris began to experiment with this technique himself. After trying out a few locations, he learned some tips from Troy Paiva, the best in the biz, and even met with Noel in Gary, IN, and Detroit, MI, to delve into more urban subject matter.

Palace Seats – Gary, IN | Christopher Robleski, 2008

On the flipside of his desert-colleagues down south, Chris’s favorite subject-matter incorporates what the northern midwest is best known for: cold and snow. While Wisconsin summers are relatively comfortable at night, temperature-wise, the air is often thick with moisture. Wisconsin winters, on the other hand, are frigid but crisp. Skies are their bluest blue and stars are breathtaking points of light, especially outside of the city. Likewise, summers coat and bury ideal subjects like vehicles deep into pastures, while the death of flora in the winters unveils the landscape’s secrets. Trust me, it’s a little tough to sport four layers of clothes and bear the sub-zero temps–especially at midnight–when a cozy, warm couch is the alternative, but it’s definitely worth the effort.

Winter Home | Christopher Robleski, 2010

Starlight Gas | Christopher Robleski, 2011

I should say, with Chris’s help on a lot of the how-to details, I’ve written this three-part piece from my perspective as a light-painting/night photography newcomer. Upon meeting Chris just over three years ago, I had absolutely no idea what light-painting was or honestly that it even existed. Chris, aka “Chocolate-Milk,” sent me a link to his Flickr photostream and I was enamored with the unique style immediately. The places he would light up were indeed abandoned, but Chris made them warm and inviting again. The reaction I had to his work doesn’t even compare to the thrill I felt the first time I went out to light-paint with Chris. Just weeks after meeting this former stranger, I agreed to an invitation that went a little something like “…there’s always a good, late night run into some creepy building. You can give a hand lighting it up. It’s a lot of fun.” Maybe I was a little nuts for taking him up the offer? But the next thing I know, I’m spending my nights traipsing through a train yard to light up a vintage passenger car, climbing inside an excavator in a run-down part of town and staying out til 2am on a ‘school night’ to drive out to an abandoned street car buried in the middle of a farm field.

Night Train | Christopher Robleski, 2009

Chris never let me by a casual bystander either. I was right there in the trenches, so to speak. And as I started talking about the adventures to my friends and family, soon others who had never heard of going out late at night during a full moon to climb around inside abandoned buildings with colored flashlights found it just as intriguing as I did.

So that gives you an idea of the What’s and the Why’s behind light-painting. In Part Two of this series, we will tackle the How. Until then, please check out the following sites showcasing the work of the aforementioned light-painting trailblazers!

The Early Years

For more information on the birth of night photography, The Nocturnes Resource has a great synopsis.

O. Winston Link: O. Winston Link Museum, Roanoke, VA

Troy Paiva: www.lostamerica.com

Additionally, for a pretty awesome glimpse at his actual film work (aka: NOT digital; aka: one-shot-is-all-you-get) from prior to 2005, check out Troy’s Flickr Set.

A great collection of some great photographers. Great inspiration for night shooting and I hope that others find this niche interesting and add to it with the advent of newer and modern equipment.

Nice article and great site.

Hey Todd! Sorry this comment slipped under our radar! Thanks for the fine compliments and we’re happy the post served as some inspiration!

[…] and taking a photo. I think it would be a better idea for you to actually go to his website for a better description. Anyway, he was a really personable guy with a great […]

thanks so much! we really appreciate it! cool blog post! I want to go play on the trains now too! at night of course!

Are you showing at any other Chicago art fairs this year?

Sue we will be at the Bucktown Arts Fest August 29 & 30th http://bucktownartsfest.com/ (no booth number yet) See you there?

These are really amazing

Thanks so much Joseph! And forgive the delayed response!